Wayback Wednesday is a series featuring historical figures with a record of military service and a connection to the Arts.

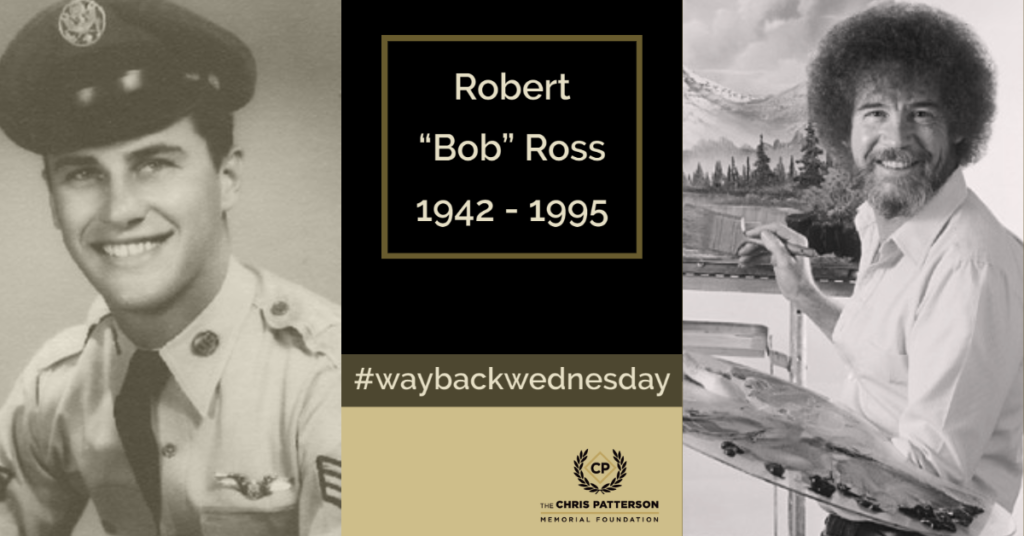

This week features Robert “Bob” Ross painter and airman.

Imagine yourself as a recently discharged airman circa 1983. Having enlisted in 1980 you’ve completed your 36 months of service, and while you are proud to have served you are also delighted to be a civilian once again. In particular, on this Sunday, you are thrilled to be watching a ball game with friends, food, and beer. You only have to find the right station on the TV for the game. As you twist the heavy nob on your set, clunking past static and stations, a face appears that stops your sojourn through the numbers. The halo of permed hair is different, as are the civilian clothes and easy smile, but there’s no doubt about it. The man on the screen, talking about “happy little clouds” is Bob ‘Bust’em up Bobby’ Ross. Your old sergeant and tour guide to hell.

Robert Norman Ross was born in Daytona Beach Florida on October 29, 1942. At age 18, he enlisted in the Air Force and was trained as a medical records specialist. Over the next 20 years, he rose through the ranks to Master Sergeant. Towards the end of his career, he found himself posted as first sergeant at Eielson Air Force Base near Fairbanks Alaska. Ross later stated it was the first time he had seen snow. Coming across such cold climes late in life Ross could have been forgiven for developing a distaste for his new posting, but instead, he quickly fell under the spell of the dramatic Alaskan landscape. After attending an art class at the Anchorage USO, Ross also fell under the spell of painting. This was despite some frustration with the teachers initially available to him, who were more interested in the philosophy of painting and abstract art. Per Ross, “They’d tell you what makes a tree, but they wouldn’t tell you how to paint a tree.”

While working part-time as a bartender on the side, Ross came across a PBS tv show called The Magic of Oil Painting hosted by Bill Alexander. Alexander used a quick-painting method called ‘alla prima’ (first attempt) or ‘wet on wet’ that allowed him to finish an oil painting in 30 minutes. This suited Ross’s personality and philosophy perfectly, and he quickly adopted this new style. During short breaks during the day, he would paint landscapes and gold rush themed scenes on the backs of replica gold-mining pans. Eventually, in 1981 Ross found himself making more from his painting than he did with the Air Force and opted to retire, heading back to Florida to study and work with Bill Alexander. In his time in the Air Force, Ross had often been “the guy who makes you scrub the latrine, the guy who makes you make your bed, the guy who screams at you for being late to work”. He decided he wasn’t going to yell again. Ever.

Ross’s wife Jane and several friends of the family convinced him he could succeed on his own in the painting business, and he parted ways with Alexander to start his own art supply company. At first, the going was slow; then, Ross got his big chance. Alexander was stepping back from his show on PBS, and the search was on for a new quick-painter to fill the niche. The Joy of Painting launched in 1983, first airing on the East Coast and the next year nationwide. The prolific Ross would go on to film 31 seasons, each of 13 episodes, over the next 11 years. The show would win 3 Emmys along the way and make Ross enough of an icon that he reluctantly chose to stick with the permed hairstyle he came to dislike because it had become a key part of his trademark. Each show, all filmed in a studio in Muncie, Indiana after the first season, was filmed in real-time with only two cameras. One medium shot, one close up. Ross became known for his calm and deliberate narrative style, and phrases such as ‘happy little clouds/trees’ inspired in part by Alexander and The Magic of Painting. He ended each episode with a variation of “… so from all of us here I’d like to wish you happy painting, and God bless, my friend …”

In the early ’90s at the peak of his fame, Ross was everywhere in pop culture making guest appearances on popular talk shows, on children’s programming (with Bill Nye and Elmo), and at the Grand Ol’ Oprey on stage with some of the Country Western musicians he loved. Sadly, his time was cut short by lymphoma, of which he died in 1995. By his own estimate, he had created in excess of 30,000 paintings.

The rise of the Internet has provided Bob Ross with an adventurous afterlife. His quick style proved perfect for YouTube and video sites such as Twitch that focus on live art, leading to an enduring interest and fame that lasts to this day. Enough so for the Smithsonian to take on the work of archiving a selection of his pictures and items from his show.

Bob Ross dedicated the first episodes of the first and second seasons of The Joy of Painting to his mentor Bill Alexander, saying “I feel as though he gave me a precious gift, and I’d like to share that gift with you.” He continues to share that gift today, a man who helped make his country both a bit safer and a bit happier and more beautiful. Today on #waybackwednesday we salute Master Sergeant Bob Ross, painter and airman.

Wayback Wednesday is a weekly series featuring historical figures with a record of military service and a connection to the arts.

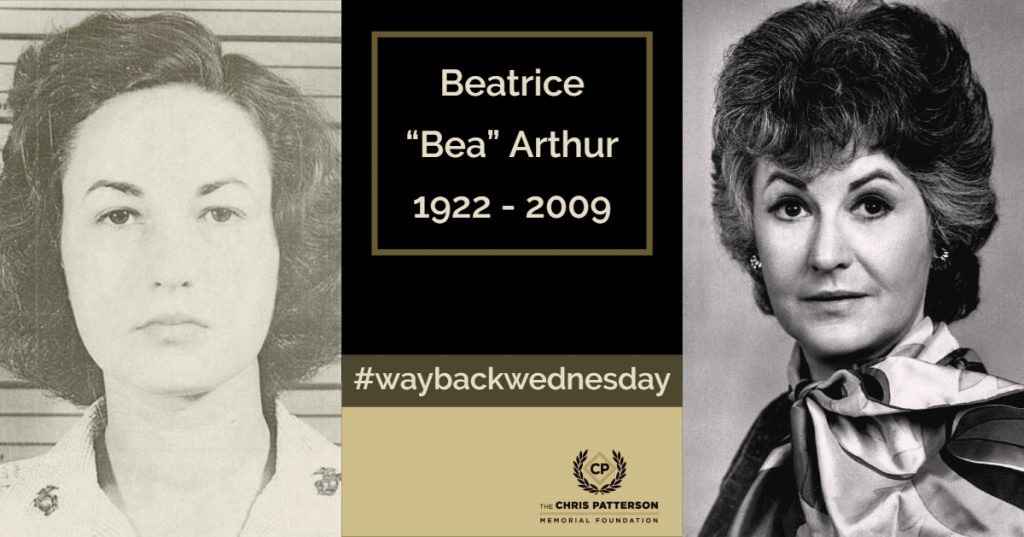

This week features Beatrice “Bea” Arthur actress, activist, and Marine.

Beatrice ‘Bea’ Arthur was born Bernice Frankel to Jewish Austro-German parents in Brooklyn, NY on May 22, 1922. After relocating to Cambridge, Massachusetts her family opened a women’s clothing shop. Quiet and introverted, though possessing a sharp wit and an early love of theater, Bea bounced through a variety of jobs before landing in 1947 at the School of Drama at the New School. Fame took some time to come by, with her breakthrough role as that of Vera Charles in the 1966 production of Mame. She had auditioned for the title role but lost out to Angela Lansbury despite husband Gene Saks directing the production. Nonetheless, the role won her a Tony for Best Featured Actress in a Musical that year. She reprised the role in the 1974 film, opposite Lucille Ball as Mame.

Bea went on to find further success on TV. She landed a role as Edith Bunker’s outspoken sister Maude in Norman Lear’s All in the Family, a role that she would go on to play for 6 seasons (1972 to 1978) in the spinoff Maude. In 1977, she was awarded an Emmy for Outstanding Lead Actress in a Comedy Series. Bea is best remembered for starring as Dorothy Zbornak in The Golden Girls from 1985-1992. Quiet and retiring in her personal life, she was notorious as a homebody who loved her family, cooking, and her dogs. She spent time as an activist for animal rights and the AIDS community. One of the stranger homages to Bea can be found in the cartoon series Teen Titans, where the character of Cyborg occasionally summons Bea’s ghost (she passed on in 2009) to win fights on his behalf. This isn’t as incredible as it first seems, given that during WWII Bea spent a year as a Marine.

On July 30, 1942, President Roosevelt signed Public Law 689, which created a women’s reserve for the Navy and Marines. Congress had dragged its feet for the past two (2) years, not wanting to pass the legislation, but it became apparent in the months after Pearl Harbor that the additional ‘manpower’ would be needed. While women would not be placed in combat roles, any administrative, maintenance, and clerical work they could perform would free up men for combat duty. Marine Commandant General Thomas Holcomb was a notorious and outspoken critic of enlisting women, and the Corps dragged its feet. By 1943, the Marines were the only branch of the US Armed Forces lacking a women’s reserve, and it was clear even to Holcomb that the help would be needed.

A late start had the advantage of being able to learn from the missteps of the other branches. Selecting from a group of 12 recommended candidates, Holcomb put 47-year-old Ruth Cheney Streeter in charge of the newly formed reserve. Streeter brought energy, dynamism, and commitment to the job. The mother of four (4), her three (3) sons would serve during the war; her brother had been killed in action in WWI. Foreseeing that war was on the horizon, she had gotten certified as a pilot in 1940 and at the outset of hostilities she had purchased a plane and joined the Civil Air Patrol. Due to her age, her repeated attempts to join the Women’s Airforce Service Pilots (WASP) were rebuffed, and she was informed in applying to the Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service (WAVES) that training or maintenance was the most she could expect to be assigned to. Standouts from the WAVES were selected as initial recruiters, and the high application standards and elite status of the Marines guaranteed high interest. Those women accepted were sent to the newly established Marine training facilities at Camp Lejeune. Streeter requested that recruits receive arms and combat training, but had to settle for demonstrations. Her philosophy was that the women of the Reserve should try anything, except combat and heavy lifting. To that end, Reserve Marines attended over 30 specialist schools during the war to acquire the training needed for the various tasks they took on.

To put it mildly, the initial Reserves were greeted with hostility. That they were commonly referred to as BAMS (Broad-Assed Marines) was among the milder bit of hazing they were subjected to. Holcomb had wanted women of character for the Reserves, though, and by and large, that is what he got. The women enlisted proved to be competent, self-assured, and proud of their contributions; they gradually won over the Corps and became a source of pride by wars end. Holcomb would state at the end of 1943, “There’s hardly any work at our Marine stations that women can’t do as well as men. They do some work far better than men. What is more, they’re real Marines. They don’t have a nickname, and they don’t need one.”

On February 18th, 1943, two months shy of 21 and just 5 days after the initial recruitment call had gone out for the Women’s Reserve, Bernice Frankel joined the Marine Corps. In her application, Bea wrote that “I was supposed to start work yesterday, but heard last week that enlistments for women in the Marines were open, so decided the only thing to do was to join.” She said she was eager to do whatever was needed. Her performance evaluations state that she was open and frank, poised, but also overly aggressive and argumentative. Overall, she did well in her time with the Corps. Following training, she served as a driver and dispatcher at the United States Marine Corps Air Station at Cherry Point, North Carolina through 1944 and 1945. By the time of her honorable discharge in September 1945, she had risen to the rank of Staff Sergeant. In her discharge paperwork, she stated that she planned to attend drama school. Lacking in glamor though her service may have been, the contributions of Bea Arthur and other women who served during WWII were still incredibly important. So, for today’s #waybackwednesday we remember the Women’s Reserve and Bea Arthur. Actress, activist, and Marine.

Wayback Wednesday is a weekly series featuring historical figures with a record of military service and a connection to the arts.

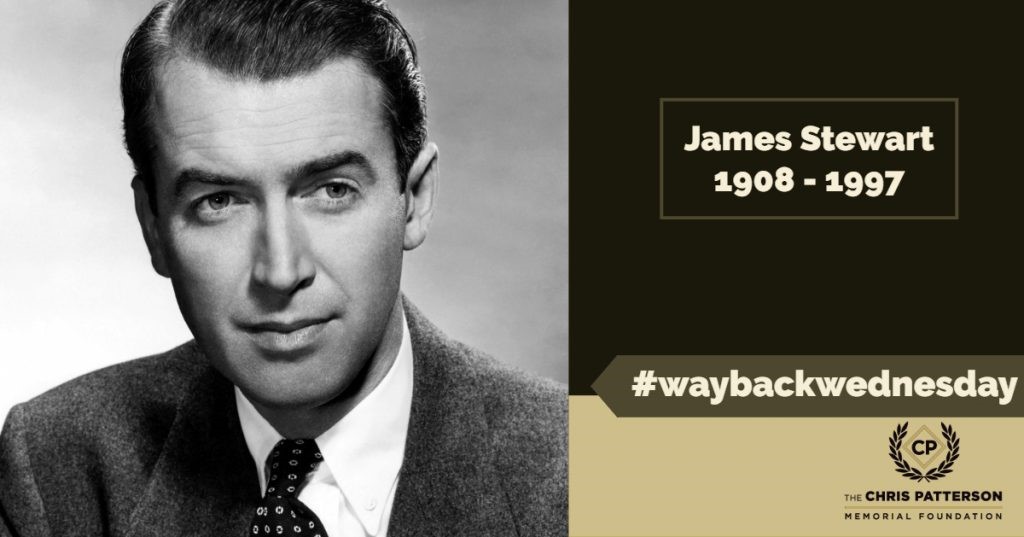

This week features James Stewart actor and WWII Air Force commander.

James (Jimmy) Maitland Stewart was born May 20, 1908 in Indiana, Pennsylvania to Scottish Presbyterian parents. Stewart’s father did not approve of his sons early interests in the arts and the military, discouraging his sons pursuit of music lessons and insisting that he attend Princeton rather than the Naval Academy after graduating from high school. Away from his family, however, Stewart’s interests had the chance to flourish. At Princeton, he joined the University Players acting troupe and met and befriended former club member Henry Fonda. With Fonda’s support (the two would be roommates in New York City for several years while they launched their acting careers) Stewart began a career as an actor after graduating in 1932. At first the plays in which he appeared gained little traction, but by 1934 he was a rising star on Broadway. With the help of Fonda, who had signed a lucrative Hollywood contract, Stewart was scouted by MGM, took a screen test, and headed west to appear on the big screen in April 1935.

Between 1935 and 1942, Stewart appeared in an astounding 26 feature films. This included what would prove to be his only Academy Award for Best Actor, for his appearance in 1940’s The Philadelphia Story opposite Katharine Hepburn. Stewart’s splash in Hollywood was also a personal one, as he was universally described as kind, soft spoken, and a true professional in his craft. The likeable and mild mannered characters Stewart is often remembered for, such as George Bailey in the 1949 Frank Capra flick It’s a Wonderful Life, were not too far from the man himself. With conflict spreading across Europe, however, James Stewart was determined to be more like George’s military hero brother, Harry.

James Stewart’s family had deep military roots; the family tree contained veterans of the American Revolution, both of Stewart’s grandfather’s had fought in the Civil War, and Stewart’s father had fought in the Spanish-American War and WWI. Stewart’s quest to serve began before the US entered WWII, with his attempts to enlist stretching from October 1940 to May 1941. The military was not terribly keen on having a celebrity aboard, particularly as war time exigencies were not yet in effect. Stewart had an ace up his sleeve, however. In 1935 he was certified as a private pilot, and in 1938 received his certification as a commercial flyer. He frequently flew cross country, following the rail lines, to visit his family back east, and even participated in a 1939 cross-country flying race as a co-pilot. At a time when the US military was in desperate need of trained pilots, the knowledge of which was part of the reason he had volunteered, Stewart was highly proficient. Initially facing rejection due to failing to meet weight requirements (he did not mass enough) Stewart was able to work with MGM trainer Don Loomis to bulk up, and was finally inducted into the Air Corps on March 22nd, 1941. As he had beat the rush to enlist, Stewart was the ‘first celebrity in uniform’ following Pearl Harbor.

The US entry into WWII removed obstacles to Stewart’s progress in the military. At 33 he was 6 years too old for the Aviation Cadet training that was the usual path to becoming an air officer. Aiming to recruit and train 100,000 young men after the outbreak of war, however, the rust was cleared away from the bureaucracy of the United States Army Air Corps and experienced flyers like James Stewart were slotted into positions of authority to steer the new recruits that were soon pouring in. Stewart was commissioned as a second lieutenant on January 2nd, 1942. Stewart’s immediate fear was that his celebrity and experience would keep him stateside working as a trainer and recruiter. And his early experience in the war seemed to bear this out in full. During 1942 and the first part of 1943, in addition to assisting (and sometimes starring in) recruitment and propaganda films, Stewart struggled to get into the fight. After three months of training on the new B-17 Flying Fortress, he was transferred to a training unit in Boise, Idaho rather than to a combat unit.

By July 1943, Stewart had risen to the rank of Captain and been qualified as a squadron commander, and rumors had begun to circulate that he was to be taken off flight duty altogether and relegated to selling bonds and starring in promotional, training, and recruiting films. At 35 and despairing of ever getting anywhere near his country’s enemies, Stewart sought the help of his 30 year old commander, Lt. Col. Walter E. Arnold. Arnold, who, to his credit, sympathized with Stewart and helped clear the way for him with a recommendation to the newly formed 445th Bomb Group of the 703rd Bombardment group. He was assigned to the 445th in August 1943, and in three weeks’ time was made its commander. Flying B-24 Liberator’s, Stewart and his squadron flew to England, and after three (3) weeks of training (during which Stewart made a point of flying with each of the combat crews in his squadron) Stewart had his wish. He flew his first combat mission on December 13th, 1943.

During his time with 445th, he would fly 12 combat missions, often deep behind enemy lines. On March 30th, 1944 Stewart was reassigned to the 453rd Bombardment Group as chief operations officer, after the 453rd had lost his predecessor (and their commanding officer) on missions. Stewart was assigned to the 453rd ‘for the duration’ and was thus no longer required to fly a certain number of missions to complete his service. He continued to assign himself for flight duty, however, initially taking charge of the lead plane on several raids deep into Germany to inspire his new unit. While official records credit him with 20 total sorties with the 445th and 453rd, Stewart had a tendency that would come into full flower following his July 1st, 1944 promotion to Lieutenant Colonel; flying uncredited. Reassigned following his latest promotion as executive officer to Brigadier General Edward Timberlake of the 2nd Bomb Wing, Stewart took on a growing number of uncredited missions with both former and new squadrons. By the end of the war, he was a full colonel in charge of the 2nd Bomb Wing.

Following the war, Stewart returned home and continued his illustrious acting career. In total between 1935 and 1991, he appeared in no fewer than 92 films, television series, and shorts. He won just about all of the highest honors it was possible to win as an actor, and in 1999 was rated by the American Film Institute as the third greatest screen actor in film history. He also continued his service as part of the Army Air Force Reserve until retiring in 1963, rising to the rank of Brigadier General and keeping current his certification on the Convair B-36 Peacemaker, the B-47 Stratojet, and the B-52 Stratofortress during his stints on active duty. During WWII, he received the Distinguished Flying Cross twice, the French Croix de Guerre, and the Air Medal with three oak leaf clusters. While happy to help with promotional materials, Stewart always steadfastly shunned any publicizing of the missions he participated in.

The aforementioned It’s a Wonderful Life offers, in some ways, a picture of the dual nature of Stewart’s time during the second world war. His service was very much a combination both of George Bailey’s hard work rallying the home front and brother Harry’s airborne heroics. To have played both roles in real life is a fitting summary of James Stewart’s contributions to both the silver screen and the United States Air Force.

Wayback Wednesday is a weekly series featuring historical figures with a record of military service and a connection to the arts.

This week features Bernardo de Galvez and his men, the shadows of whom still live on in the corners of the Marine Hymn.

Adopted in 1929 as the official song of the United States Marine Corps (USMC), the Marine Hymn is the oldest official song of the US Armed Forces. It is usually sung by the Corps at attention as a gesture of respect, and most adults in the US can readily recognize the song and provide a few of the lyrics. The song begins:

From the Halls of Montezuma

To the shores of Tripoli;

We fight our country’s battles

In the air, on land, and sea;

First to fight for right and freedom

And to keep our honor clean;

We are proud to claim the title

Of United States Marine.

Like the whole of the song, a great deal of history of the USMC and the country they fight to protect is caught up in the very first line, ‘From the Halls of Montezuma.’ This opening line is a reference to the September 12-13, 1847 Battle of Chapultepec, during which 400 Marines on detached duty led the storming of an imposing bastion at what would prove to be the defining moment of the Mexican War. Chapultepec was a fitting place for the fight, given its connection to an iconoclastic Spanish Viceroy and a band of militia in the American Revolution.

In 1785, the construction of Chapultepec Castle was ordered by newly appointed Viceroy Bernardo de Galvez as a summer home for the Viceroyalty. Galvez had earned the posting through his actions as governor of Spanish Louisiana. The strategic port of New Orleans, a back door to the colonies, proved critical in the early years of the Revolution as a road for smugglers and haven for privateers.

As Governor-General, Galvez carried out with enthusiasm his government’s desire to covertly support the Americans. Working with an agent of the fledgling United States, Oliver Pollock, Galvez strove to ensure the efficient acquisition and transport of supplies up the Mississippi River, commissioning new trails to make the trip easier. As Spain was ostensibly neutral, New Orleans could not be blockaded and the British had too much already on their hands to protest too strongly Galvez’s protection of privateers and smugglers. Things became more complicated in 1779 when Spain, like France and the Netherlands, entered the war on the side of the Thirteen Colonies.

Days after Spain’s declaration of war on Great Britain, a letter was sent from King George III and Prime Minister Lord St. Germain to General John Campbell at Pensacola in British Florida, instructing him to begin organizing an attack on New Orleans. The letter fell into allied hands, and was brought to Galvez. The British campaign was to be dependent on gathering forces from across the Caribbean; Galvez quickly and quietly began organizing an expedition to attack first.

On August 21st, Galvez set out from New Orleans with a force of 520 regulars (2/3rds recent volunteers), 60 militiamen, 80 free blacks, and 10 American volunteers led by the intrepid Mr. Pollock. Journeying north to attack the British stronghold at Baton Rouge, local Creoles, Indians, Tejanos, and Hispanics swelled his numbers to 1,400. After a delaying action by the British at Fort Bute, Galvez pressed on to besiege the 400 British soldiers at Baton Rouge. After eight days, caught off guard and not expecting to be on the defensive, the British surrendered. Having secured the lower Mississippi against British interference, Galvez garrisoned his newly won territory and returned to New Orleans.

On January 20, 1780 Galvez set sail with a force of 1,300 men, which he soon had ashore below Fort Charlotte on the approaches to Mobile. The British force of 304 soldiers and militia put up a spirited defense, but was forced to surrender after the walls were breached by Spanish artillery.

In the fall of 1780, the British at Pensacola, now their last stronghold in the region, were given extra time to prepare their defenses when Galvez next assault expedition was dispersed by a hurricane. Galvez was not delayed long, regrouping and getting an army to Pensacola by March 1781. General Campbell had thought, following the hurricane, that he had an opportunity to seize the initiative and was caught with some of his forces away from Pensacola’s fortifications. Still, Campbell had pulled together a total of 1,300 regulars, Indians, and militia. While the Spanish started with only a small advantage in numbers, Galvez had arranged for the flood of reinforcements, supplies and laborers needed for a long siege. By May of 1781, the Spanish had overwhelming force available. Under ever heavier bombardment, with their outer fortifications having fallen to the Spanish force, the British garrison surrendered on May 8, 1781.

When the war ended in 1783, Galvez was in the process of planning the conquest of British Jamaica. His efforts and those of his men denied the British the possibility of a second front against the colonists, ensured supply lines to the Continental Army through the Gulf or Mexico, and effected the forces on both sides during the final battles of the war. Additional French and Spanish soldiers and ships were available for the Yorktown campaign, while the British had to contend with reinforcing their now vulnerable Caribbean possessions.

For his efforts, Galvez was recognized by the Continental Congress and by General George Washington himself. He is remembered through a smattering a street names in Louisiana and Florida, a statue in Washington DC erected in 1976 for the centennial, and in one large city that bears his name (Galvezton, TX). He was rewarded with the Viceroyalty of Cuba and then of all New Spain in 1783. In addition to commissioning Chapultepec Castle, Galvez sponsored a botanical expedition, patronized the arts, donated a portion of his annual salary to charity, and in general continued to be an energetic and effective leader.

Alas, Spain’s imperial decay began to catch up with him. In a weakening empire, the best and brightest were increasingly subject to official skepticism and sanction. Before the full weight of official displeasure could catch up with him, Galvez died at the age of 40 on November 30th, 1786. Suspicions of possible poisoning persist to this day, though a typhoid epidemic was likely the culprit. In 2014, he became one of only eight individuals in history awarded honorary United States citizenship. In his energy, curiosity, and lack of concern for those conventions that he deemed unhelpful, Galvez was perhaps better representative of the New World than the Old that he had pledged service to. As for the troops that fought with Galvez, they would wait close to 25 years before securing their portion of the freedom won in the war they had fought. With the 1804 conclusion of the Louisiana Purchase, they gained their American citizenship.

A bit messy and somewhat unlikely, like the United States itself, today for #waybackwednesday we honor Galvez and his men, the shadows of whom still live on in the corners of the Marine Hymn.

Update: A quick note following up on Wednesday’s posting, regarding the Marines who participated in the assault on Chapultepec. A total of 400 Marines were present with General Winfield Scott in 1847 as he attempted to take the capitol of Mexico City by circling to the west. Chapultepec Castle, on a rise of 200 feet, guarded that approach and would have to be taken. After having to persuade most of his officers that attacking the imposing height was advisable, Scott set the attack for September 13th. September 12th was spent in bombardment and positioning troops. Three enveloping forces totaling 2,000 soldiers, under Generals Gideon Pillow, William Worth, and John Quitman were to go forward. Preceding these troops were two storming parties of 250 men each, commanded by Major Levi Twigg and Captain Samuel MacKenzie. These two parties, which included 40 Marines with Twigg, were considered ‘forlorn hopes’ intended to come to blows with the enemy as quickly as possible and draw almost certainly fatal amounts of the defender’s attention.

They indeed took hideous casualties, but proceeded on ahead of the attack rather than falling back. Upon reaching the walls of Chapultepec, hideous hand to hand fighting ensued with neither side seeking or giving quarter. It was here, having reached the walls, where the Marines tenacity helped carry the day. At the forefront of the push into the castle itself, the famed ‘Halls of Montezuma.’ When General Scott entered the castle after the battle, he found the streets inside guarded by the surviving Marines. A remarkable testament, given their exhausting contribution to the fight, the chaos and disorganization that usually accompanies a hard fight for any strong point, and the fact that 90% of the Marine officers and noncommissioned officers who participated in the fight were casualties.

In addition to the reference in the Marines Hymn, the scarlet ‘blood stripes’ were added to Marine dress uniforms in memory of the fallen at Chapultepec. The Marines had been around since their formation by an act of the Second Continental Congress on November 10th, 1775 (thus preceding the Declaration of Independence). As odd as it may sound today, the USMC lacked in its early history the esprit de corps and hard-hitting aura that it possesses today. It was not long before the American Revolution, after all, that Samuel Johnson expressed the opinion of many in the English speaking world about service aboard a ship when he wrote, “No man will be a sailor who has contrivance enough to get himself into a jail; for being in a ship is being in a jail, with the chance of being drowned… a man in a jail has more room, better food, and commonly better company.” The reputation of the United States Marine Corps was earned, not given, in hard fighting and blood. Some done in battles remembered still in song, such as Chapultepec, and others in fighting that is today largely forgotten.

Wayback Wednesday is a weekly series featuring historical figures with a record of military service and a connection to the arts.

This week features Chicagoan and member of the WWII Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives (MFAA) program, Richard Barancik.

An army is a complicated thing, with many different roles to play and not all impacts on civilian life easily foreseen. In 1943, with WWII in full swing, a group of men and women with unique training were given a special task. Their unique skills were in the arts and preservation, and their task was to safeguard (and sometimes find, if they had been relocated during the German occupation) cultural monuments across Europe.

War in the 20th century was, to put it mildly, hugely messy. And Europe, particularly without its current modern infrastructure, was a fairly big place with lots of art and monuments for the 400 individuals of the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives (also known as the ‘Monuments Men’) program to track down and protect. It was not perhaps the most heroic posting in the army, but the members of the MFAA were dedicated to what they did. They provided intelligence to army and air force officers that allowed them to, as possible, minimize damage to museums, monuments, and structures of historic significance. Far from using the their posting to hang back, MFAA personnel often arrived in liberated communities just after the Germans had left and before allied troops entered. Captain Walter J. Huchthausen, who was killed by gunfire while trying to salvage an altarpiece, and Major Ronald Balfour, killed by a shellburst while scouting for hidden artworks beyond allied lines, are symbolic of their dedication.

At the age of 18, Chicagoan Richard Barancik joined the Army Enlisted Reserve Corps in December of 1942. In 1943 he attended the Army Specialized Training Program (ASTP) and attended basic engineering courses at the University of Nebraska. In 1944, he was sent to Europe with the 66th Army Division. Originally headed for the Battle of the Bulge, the 66th was instead sent to besiege the German fortifications at St. Nazaire after 700 soldiers were lost when their transport ship, the SS. Leopoldville, was torpedoed. Barancik then headed to Southern France before being reassigned to Austria, where he came across the MFAA cataloging, archiving, and repairing caches of art hidden by the Nazi leadership. He immediately volunteered for service with the MFAA and was accepted. Barancik recalled later that, “When I arrived in Salzburg, I was not only overwhelmed by the beauty of the town but the quality of the men in the Fine Arts Section. They were typically older and very well educated in the Fine Arts.” Following the war, Barancik would manage to pile up achievements worthy of the company he had been keeping. Barancik studied architecture at the University of Cambridge in 1946 and at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts at Fontainebleau, France in 1947. He received his Bachelor of Science in Architecture and Bachelor of Science in General Studies at the University of Illinois in 1948. From 1950 to 1993, he enjoyed a long and prosperous career as a prominent Chicago architect.

Other, similarly motivated and talented members of the MFAA went on to help found the National Gallery of Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the New York Ballet along with a slew of smaller museums and institutions across Europe and the United States. An outcome from the chaos of WWII no less welcome for being so unexpected. War is, after all, as much (if not more) what is protected as who you fight. And Barancik and the other members of the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives program exemplify this in their unusual service during WWII. They probably deserved a better movie than the 2014 Monuments Men. I recommend the book Monuments Men: Allied Heroes, Nazi Thieves and the Greatest Treasure Hunt in History by Robert Edsel, which is much better, if you would like to learn more.

Wayback Wednesday is a weekly series featuring historical figures with a record of military service and a connection to the arts.

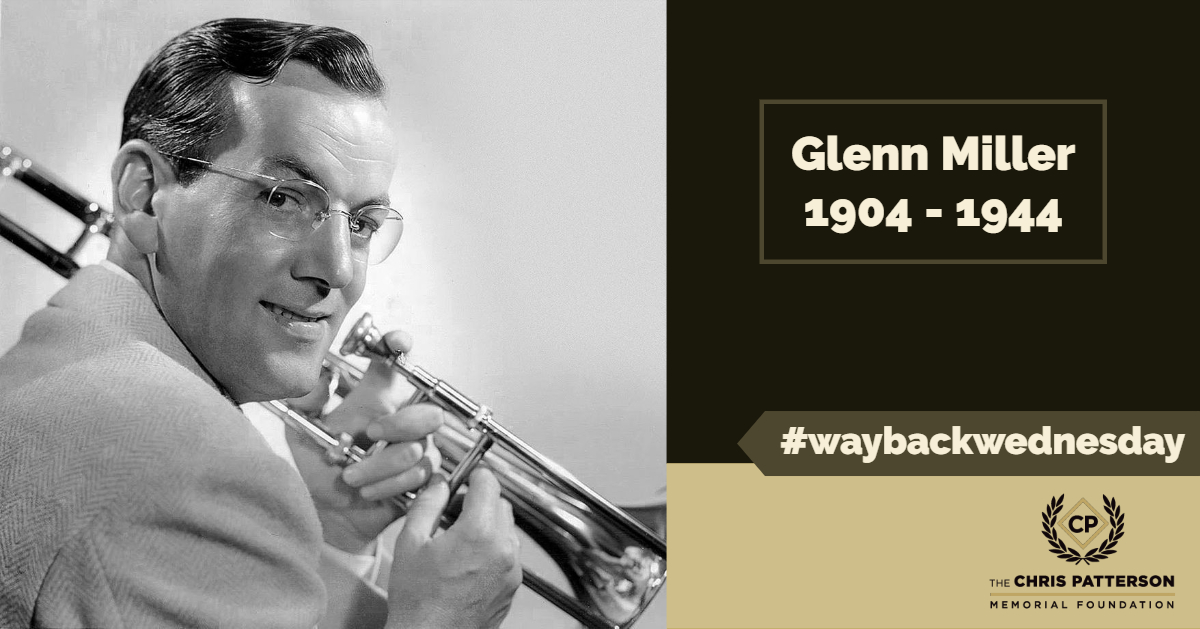

This week features big-band leader, Glenn Miller.

When Glenn Miller broke through onto the music scene in 1938, he was already 34 years old and had spent years on the big band circuit without achieving the success he craved. Finally having landed on a unique sound and assembled the right band members to deliver on his arrangements, his Glenn Miller Orchestra landed a new contract with Bluebird Recording and was able to book a series of prominent live shows. To say they became famous is an understatement; between 1939 and 1942, Miller would log 17 number one records and 59 top ten hits. For those keeping score at home, the Beatles had 33 top ten hits, and Elvis Presley had 38. In 1942, however, Miller was determined to set aside his hard won fame and contribute to the war effort. At the peak of his fame and earning between $15,000 to $20,000 per week, which would still be pretty fantastic in 2019, Miller first had to find a way to get into a then-hard-pressed military wary of more bad press.

At 38, Miller was too old to be drafted and so sought to volunteer his services. He first offered his services to the Navy, who turned him down. Changing tack, he wrote to Army Brigadier General Charles Young and asked to “be placed in charge of a modernized army band.” On October 8, 1942 he reported for duty in Omaha, NE for service with the Seventh Service Command in the Army Specialist Corps. Miller quickly set to work revolutionizing the army band, with his fame and the war effort paving the way past unhappy traditionalists. Based in New Haven, CT and then New York City, Miller and his band performed a weekly radio broadcast entitled I Sustain the Wings. In 1944 he won permission to form his 50 piece Army Air Force band and take it to England, where they gave over 800 performances. While there, Miller and his band recorded a series of their songs in German for use on propaganda broadcasts.

On December 15th, 1944 Miller boarded a small plane headed for Paris, scouting ahead as he planned for the City of Lights to be the next stop for his AAF band. Despite his distance from the front, Miller had had his close calls already. After a bomb landed within three blocks of his offices in London he was persuaded to relocate, as it does not do to have the enemy blow up your morale effort. The day after leaving, a V-1 flying bomb struck the building, killing 70. Now, with bad weather closing in, Miller’s flight disappeared over the channel. Wreckage was never found, leading to years of conspiracy theories. The UC-64 Norseman he had been flying aboard had a carburetor that was notorious for icing up in cold weather. He was 40 years old, and left behind a wife and two adopted children. They accepted the posthumously awarded Bronze Star on his behalf.

Miller’s musical work continued to have an impact down through the years, often inspiring (and being imitated by) other artists. Former band members formed a ghost band, dedicated to performing Miller’s work. After a few fits and starts, with disagreements between former band members, in 1956 an official ghost band ‘stuck.’ The band is still touring the United States today, a testament to Miller’s lasting popularity and enduring musical contributions. While Miller’s AAF Band was disbanded in 1945, its influence can be felt throughout the armed forces to this day. After WWII, most branches added a jazz band to their concert and marching bands. Music remains an important part of the American military tradition to this day. Miller would have had it no other way, stating in one of the propaganda recordings that, “America means freedom and there’s no expression of freedom quite so sincere as music.”

Wayback Wednesday is a weekly series featuring historical figures with a record of military service and a connection to the arts.

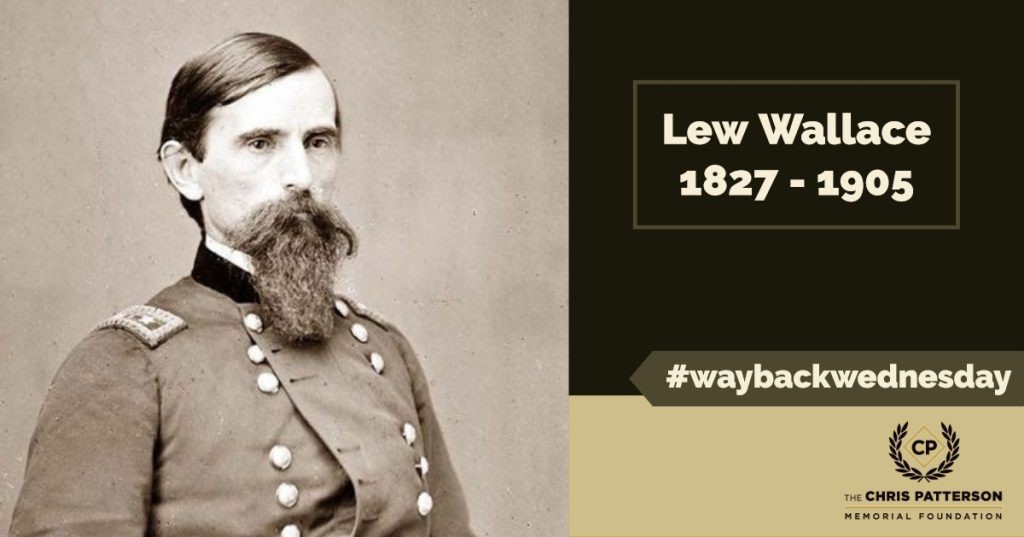

This week features one of the most famous Hoosier’s to grace the literary scene, Lewis ‘Lew’ Wallace.

In 1880, Wallace published the novel Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ. The book quickly became a bestseller, and ranked as the top all-time bestselling novel until the 1936 publication of Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind. The book is widely considered the ‘most influential Christian book of the 19th century and the 1959 film version netted 11 Academy Awards. Unless you’ve recently emerged from a cave (and if you have, ‘Congrats!’) you’ve probably heard of it because it was (and in many ways still is) kind of a big deal. The connection to Gone with the Wind is particularly interesting, though, given that Wallace also served in the Union Army during the Civil War helping to add the Antebellum to the heavily romanticized South of Mitchell’s novel.

As he was a prominent Republican, attorney, and newspaperman, who had served as a First Lieutenant in the Mexican War, the governor of Indiana asked Wallace to act as Adjutant General for the state at the outbreak of the Civil War in 1860, and that he take charge of filling the required recruiting quotas. Wallace agreed provided that he be allowed to take active military service once the levy was met, and received command of the 11th Indiana Volunteers after Indiana’s six regiments were filled in only a week. He quickly gained the attention of his superiors and rose through the ranks during the small engagements in the West at the start of the war. He gained distinction and a promotion to Major General (the youngest in the Union Army at 34) by fending off a Confederate breakout attempt during Grant’s siege of Fort Donelson, and leading the counterattack that ensured no breach remained to be exploited.

Wallace’s best-known Civil War exploit, however, was his unfortunate roundabout march bringing his division to the field at the Battle of Shiloh. In the confusion and recriminations after that battle, which would dog Wallace the remainder of his life, he was transferred to a non-combat post. Late in the war, however, Lew Wallace would find the opportunity to redeem himself as the commander of the defense of Washington DC during an 1864 attempt by Lieutenant General Jubal Early to seize the sparsely defended capitol. Recognizing that time was critical for reinforcements to reach Washington, Wallace gathered 6,800 largely untested troops at critical Monocacy Junction. Sparring with the advancing Confederates and forcing them to deploy for a full scale battle, Wallace’s troops held out for a full day; despite being outnumbered 3 to 1, withstanding five full assaults, and retreating in good order. When Early arrived before the fortifications outside Washington DC, it was to the sight of the Union VI Corps filing in opposite his army. Hearing of the defeat, and remembering Wallace from Shiloh, Grant removed him from command after Monocacy Junction. However, after reviewing the full reports of the battle, he returned Wallace to command. In his memoir, Grant wrote that, “If Early had been but one day earlier, he might have entered the capital before the arrival of the reinforcements I had sent …. General Wallace contributed on this occasion by the defeat of the troops under him, a greater benefit to the cause than often falls to the lot of a commander of an equal force to render by means of a victory.”

Lew Wallace would continue to have an interesting life post-war, serving as ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, Governor of the New Mexico Territory, and for a time as a general in the Mexican Army. He attempted to enlist for the Spanish American War when in his 70’s, but was turned down twice (as an officer and again when he tried to enlist as a Private). And he also found the time to write one of the bestselling novels of all time, of course. So, on our first #WaybackWednesday, we remember Lewis ‘Lew’ Wallace and the service, on and off the battlefield, that he provided to his country.