Wayback Wednesday is a weekly series featuring historical figures with a record of military service and a connection to the arts.

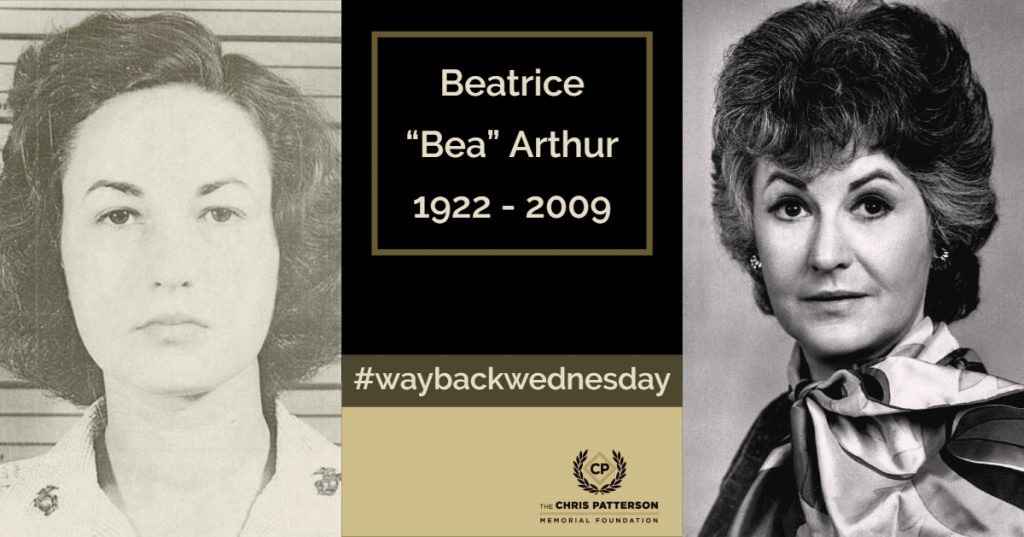

This week features Beatrice “Bea” Arthur actress, activist, and Marine.

Beatrice ‘Bea’ Arthur was born Bernice Frankel to Jewish Austro-German parents in Brooklyn, NY on May 22, 1922. After relocating to Cambridge, Massachusetts her family opened a women’s clothing shop. Quiet and introverted, though possessing a sharp wit and an early love of theater, Bea bounced through a variety of jobs before landing in 1947 at the School of Drama at the New School. Fame took some time to come by, with her breakthrough role as that of Vera Charles in the 1966 production of Mame. She had auditioned for the title role but lost out to Angela Lansbury despite husband Gene Saks directing the production. Nonetheless, the role won her a Tony for Best Featured Actress in a Musical that year. She reprised the role in the 1974 film, opposite Lucille Ball as Mame.

Bea went on to find further success on TV. She landed a role as Edith Bunker’s outspoken sister Maude in Norman Lear’s All in the Family, a role that she would go on to play for 6 seasons (1972 to 1978) in the spinoff Maude. In 1977, she was awarded an Emmy for Outstanding Lead Actress in a Comedy Series. Bea is best remembered for starring as Dorothy Zbornak in The Golden Girls from 1985-1992. Quiet and retiring in her personal life, she was notorious as a homebody who loved her family, cooking, and her dogs. She spent time as an activist for animal rights and the AIDS community. One of the stranger homages to Bea can be found in the cartoon series Teen Titans, where the character of Cyborg occasionally summons Bea’s ghost (she passed on in 2009) to win fights on his behalf. This isn’t as incredible as it first seems, given that during WWII Bea spent a year as a Marine.

On July 30, 1942, President Roosevelt signed Public Law 689, which created a women’s reserve for the Navy and Marines. Congress had dragged its feet for the past two (2) years, not wanting to pass the legislation, but it became apparent in the months after Pearl Harbor that the additional ‘manpower’ would be needed. While women would not be placed in combat roles, any administrative, maintenance, and clerical work they could perform would free up men for combat duty. Marine Commandant General Thomas Holcomb was a notorious and outspoken critic of enlisting women, and the Corps dragged its feet. By 1943, the Marines were the only branch of the US Armed Forces lacking a women’s reserve, and it was clear even to Holcomb that the help would be needed.

A late start had the advantage of being able to learn from the missteps of the other branches. Selecting from a group of 12 recommended candidates, Holcomb put 47-year-old Ruth Cheney Streeter in charge of the newly formed reserve. Streeter brought energy, dynamism, and commitment to the job. The mother of four (4), her three (3) sons would serve during the war; her brother had been killed in action in WWI. Foreseeing that war was on the horizon, she had gotten certified as a pilot in 1940 and at the outset of hostilities she had purchased a plane and joined the Civil Air Patrol. Due to her age, her repeated attempts to join the Women’s Airforce Service Pilots (WASP) were rebuffed, and she was informed in applying to the Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service (WAVES) that training or maintenance was the most she could expect to be assigned to. Standouts from the WAVES were selected as initial recruiters, and the high application standards and elite status of the Marines guaranteed high interest. Those women accepted were sent to the newly established Marine training facilities at Camp Lejeune. Streeter requested that recruits receive arms and combat training, but had to settle for demonstrations. Her philosophy was that the women of the Reserve should try anything, except combat and heavy lifting. To that end, Reserve Marines attended over 30 specialist schools during the war to acquire the training needed for the various tasks they took on.

To put it mildly, the initial Reserves were greeted with hostility. That they were commonly referred to as BAMS (Broad-Assed Marines) was among the milder bit of hazing they were subjected to. Holcomb had wanted women of character for the Reserves, though, and by and large, that is what he got. The women enlisted proved to be competent, self-assured, and proud of their contributions; they gradually won over the Corps and became a source of pride by wars end. Holcomb would state at the end of 1943, “There’s hardly any work at our Marine stations that women can’t do as well as men. They do some work far better than men. What is more, they’re real Marines. They don’t have a nickname, and they don’t need one.”

On February 18th, 1943, two months shy of 21 and just 5 days after the initial recruitment call had gone out for the Women’s Reserve, Bernice Frankel joined the Marine Corps. In her application, Bea wrote that “I was supposed to start work yesterday, but heard last week that enlistments for women in the Marines were open, so decided the only thing to do was to join.” She said she was eager to do whatever was needed. Her performance evaluations state that she was open and frank, poised, but also overly aggressive and argumentative. Overall, she did well in her time with the Corps. Following training, she served as a driver and dispatcher at the United States Marine Corps Air Station at Cherry Point, North Carolina through 1944 and 1945. By the time of her honorable discharge in September 1945, she had risen to the rank of Staff Sergeant. In her discharge paperwork, she stated that she planned to attend drama school. Lacking in glamor though her service may have been, the contributions of Bea Arthur and other women who served during WWII were still incredibly important. So, for today’s #waybackwednesday we remember the Women’s Reserve and Bea Arthur. Actress, activist, and Marine.